All three of the stories in this reading are about artists who are obsessed with their art. Both the trapeze artist and the starvation artist are so devoted to their respective arts that they don’t want to encounter the real world. Josefine struggles and is damaged by her interaction with the real world and her audience. None of them want anything to challenge or hinder their art or their artistic process. The first two stories consider the artists, whilst the last focuses more on the audience.

The relationship between the artist and the audience progresses with each story, beginning with the trapeze artist who never wants to come to earth. (The part where Kafka explains how the manager uses the fastest race cars to move the trapeze artist from town to town gave me the weirdest picture in my head because I imagined tall poles bolted to the sides of a convertible with the trapeze artist and his trapeze swinging high up between them. Perhaps the manager should have thought of this. Maybe it would have made the trapeze artist happier. Too bad he existed in the days before air travel!) I see this as an idealized metaphor for the way an artist sees himself; that if the demands of the real world didn’t force him down to earth now and then, he would spend his days and nights doing nothing besides making art. Artists seldom get to experience this, however, because the real world—or gravity—cannot truly be overcome.

My thought in relation to this particular idea is this; if the artist were allowed to exist solely without the interruptions of the real world, would he not get bored? How will he look forward to making art when he has no boredom or tedium to contrast it with? When he has no lack of art, can he be satisfied with round-the-clock art? What happens when there is no black to contrast the white, no evil with which to define good? TA (from now on I will refer to the trapeze artist as TA and the starvation artist as SA, because it takes too long to type their names over and over) gets to the point where he really has no contrast for his art, so he has to make one up. One trapeze is no longer good. Now, only two trapezes can satisfy him and he looks back with horror on his former single-trapeze act. His creativity is flourishing—no one ever thought of doing the act with two trapezes before!—but at the same time he can never be satisfied. He is either going to drive himself mad or worry himself to death, hence the wrinkles. I think this can apply to anything in life. If you could do whatever you wanted all the time and never had to do a single thing you didn’t want to—not even visit the dentist—would you get bored? Would you live longer or die sooner than others who had to balance their time between odious chores and having fun?

What is the price of absolute freedom? When I think of SA, two things come to my mind, the first is the term “failure to thrive,” which is the term biologists and doctors use when babies die. The second is that when Kafka describes SA in his black leotard, I picture Willem Defoe in Shadow of the Vampire. Poor SA, all he wants to do is starve, but when he gets to have all the time he wants to starve, people stop caring. This is just one possible consequence of the complete artistic freedom that TA yearns for. The theme of never being satisfied is echoed in the dying words of SA when he explains that he “never found the food [he] liked,” (94). Isn’t this a metaphor for not ever being satisfied? But if SA had found the food he liked, he wouldn’t have an art. Perhaps he just tells himself that he doesn’t like any food to justify his art? Because it seems like kind of a cop-out, coming at the end of the story and all—is he just rationalizing?

Josephine has some problems with regard to her audience. They are so busy forcing her to perform and conform to the way they think she should be that in the end she and her art are lost. It seems like the narrator of this story is the collective voice of all of the Mouse People, and the way they treat Josephine reminds me not only of the way critics and scholars treat writers and artists, but also how tabloids treat celebrities. They are at the same time proud of her talent and jealous of it. She’s the greatest singer ever, but her voice isn’t any different than anyone else’s—or is it? Why is she the greatest singer? Why is she more special than the rest of them? How can she be better than them at this thing if all Mouse People are created equal (I wonder if Kurt Vonnegut read this before writing Harrison Bergeron)? They want her to be superhuman, (or super-Mouseman?), and at the same time just like all of them—how dare she get old! How dare she refuse to sing! They want to use her and her art to define the identity of their whole people, and they can’t ever be satisfied with her or her art because she isn’t superhuman. They revere her for her talent at the same time they resent her for it. They can’t stop themselves from doing this any more than the starvation artist can help starving. Does the art belong to the artist or to the audience?

I am especially interested in the questions posed at the beginning of this story—how is Josephine’s “squeak” so great when it is just a squeak like all others? Why is it that what one artist says is better or different than another? We all have something to say, but society only considers what some of us have to say as “art.” Who says what’s good and what isn’t? This is an interesting question to contemplate in modern times when the blogosphere makes it possible for any wannabe writer to smear his brains all over the Internet. Most people shouldn’t. What sets people like David Sedaris apart, people who can relate (slightly or not-so-slightly exaggerated) anecdotes about daily life so much better than those bloggers? I have several books by a guy named Al Burian who self-publishes stuff that is also very similar to what bloggers write (personal anecdotes and personal philosophies), but it is better. It is so much better that his self-published zine, “Burn Collector,” is popular across the US and probably in Europe—these crappy little things that he used to make at Kinko’s and still are put together by hand (part of the zine aesthetic)—but why have I read them all a hundred times? Maybe it’s because he writes things like this:

“If any doubt remained as to [former mayor of

Tuesday, January 29

The Tribulations of Artists

Saturday, January 26

Marinated Potatoes, How I Love Thee

My parents took me to

Our favorite dish was the make-your-own taco extravaganza served in the hotel’s Mexican restaurant, which served a mix of authentic and Tex Mex dishes. The make-your-own taco dish was served in two or three earthenware platters with molded sections to hold all the taco ingredients. These included avocadoes, skirt steak, chicken, pork, onions, cilantro, and tomatoes. My two favorite things were the pool of melted white cheese, (up to this point I hadn’t met a white cheese I liked), and the marinated baby potatoes. I first thought the baby potatoes were cocktail onions and wouldn’t touch them. I soon discovered they were not cocktail onions and realized instead that they were vinegary and herby and that potato skins could actually be good.

I am reminded of my marinated Mexican potatoes when Hemingway takes himself to lunch at Sylvia Beach’s insistence and orders for himself beer, potato salad, and sausage on page 72 of A Moveable Feast. I wonder how a person can remember so much detail from something that happened almost 40 years prior, then I realize I never would have remembered the lizards at the café in

I think taste can be an even stronger link to memory than smell. Since he has prefaced this work with the words, “this book may be regarded as fiction,” Hemingway may be fabricating some details of his meals, but I think it’s possible to remember exactly what one ate on a certain occasion. While in

Another thing that strikes me about this particular meal is the fact that beer, potato salad, sausage, and bread constitute a meal of comfort food—especially for a man raised in the

What I do know is that I cannot read the line, “[t]he pommes a l'huile were firm and marinated and the olive oil delicious,” without remembering my own marinated potatoes, and over the weekend I had to make myself some French potato salad and sausage and eat it with bread and beer. It was delicious.

Thursday, January 24

One of the most interesting things about “In the Penal Colony” is the fact that it didn’t end like I expected it to. The whole time I was reading it, I was expecting that the officer would find something wrong with the conduct of the traveler and condemn him to death in the machine. I think such an ending would make it more of a horror story, and if it had been written by someone like Poe the ending would have gone more like this: the officer tells the condemned man that he is “free” and the traveler finds out the whole thing has been an elaborate scheme to get him into the machine. The condemned man, soldier, and officer have all been working together in an elaborately staged ruse, and they seize the traveler and strap him into the machine, whilst the others on the island crowd around to watch. It would be hinted at—but left ambiguous—as to whether the traveler was being put into the machine simply because the officer and the other prisoners in the colony are depraved and enjoy tricking people into the machine, or whether the traveler has done something that caused his home government to condemn him to death and send him here.

I think part of the reason I expected this to happen is because the officer so fervently worships the machine that its existence has become more important to him than the death sentences for which it was created. This is evident on page 46 when the officer complains about the fact that it takes 10 days to get a new strap for the machine and wonders how on earth he’s supposed to use it in the meantime. He doesn’t consider holding off on the death sentences during this time. The fact that the machine exists, for him, means that he must always be condemning men to death in order to put it to use. I wonder if there even were death sentences in the colony before the advent of the machine. I also wonder if the machine were in better condition and didn’t break down or wear out parts so often, if the officer and the former commandant would have gone through all the prisoners on the colony and started finding others, such as the dockworkers, to feed the machine. It makes me think of something a child would do when given a rock polisher, for instance, and has to find every rock within a three-mile radius of his home in order to polish it, because using the rock polisher is so fun. The officer definitely seems to have a childlike personality, which adds to his creepiness.

I am reminded a little bit of La Bete Humaine, because both the officer’s and Jacques’ existences are so bound up in killing. Jacques has an irresistible urge to kill women simply because they, and whatever they represent for him, exist. He can fight the urge as long as he is not near a woman. Kafka’s officer must kill men because the machine exists, and as long as the machine exists, he feels that he must make use of it. As I said earlier, if the machine didn’t exist, the officer would have not reason for death sentences, but he is too weak to resist his nearly religious obsession with it. In the same way, Jacques wouldn’t need to kill anyone as long as he never encountered a woman, but whenever he sees one, he feels that he must kill her simply because she exists, and he has a hard time overcoming this urge due to weakness.

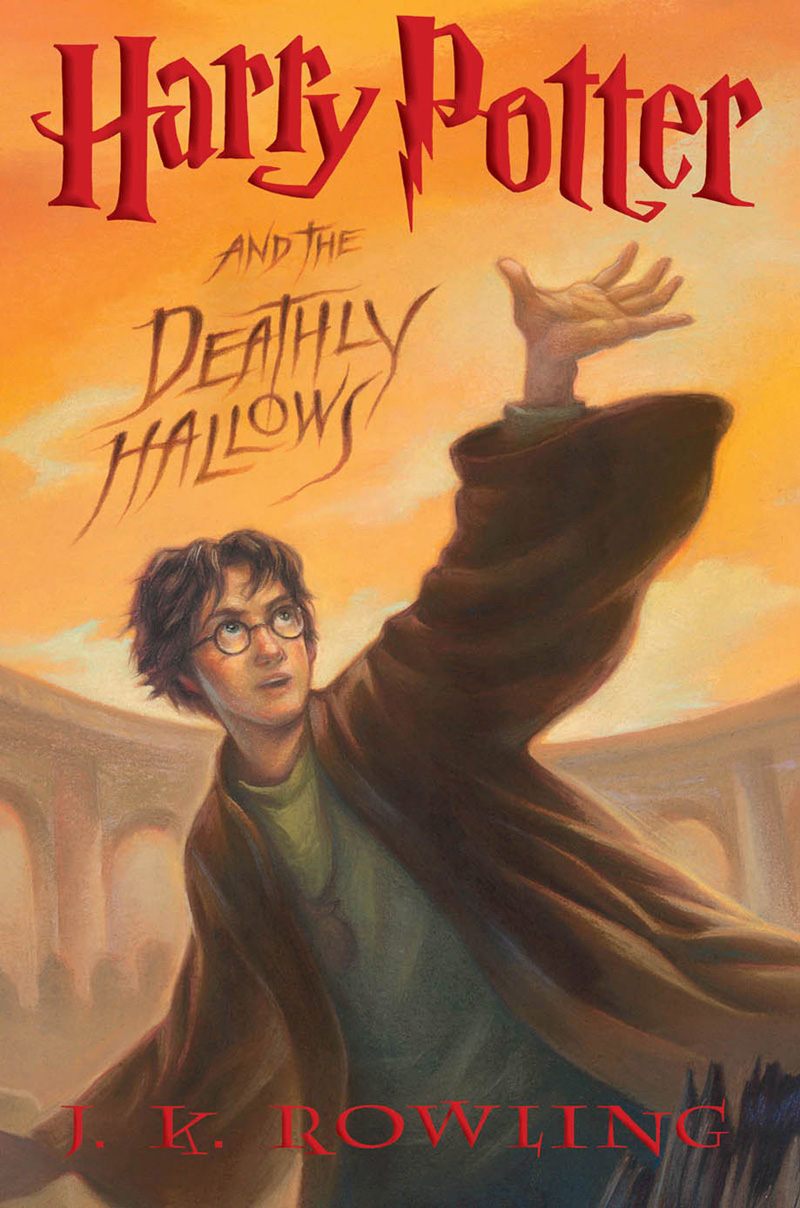

This story is referenced in, of all things, a Harry Potter book. Harry is sentenced to write lines as punishment, and a magical spell causes the words he writes to be scratched into the skin on his hand, leaving a permanent scar reading, “I will not tell lies.”